by Paul Alexander Wolf 🇦🇺

There are places that never leave you, even long after you’ve left them. Siloam Hospital in Venda is one of those places – a landscape of red dust, endurance, fragile systems, and a kind of stubborn human courage that never needed praise to be real. And at the centre of that world stood two people who never tried to be extraordinary: Dr Evert Helms and his wife, Dr Leida Helms. They didn’t speak about sacrifice. They didn’t dramatise their service. They simply stayed. And by staying, they shaped a region.

Their journey to Venda began because someone saw what Siloam needed before they did. Professor Koos van Rooy, the mission theologian who first served in Siloam in the late 1950s and later became central to the Venda Bible translation, recognised in Evert the precise kind of long-haul doctor a rural mission hospital needed. Koos lived on a small rise called “Het Kopje”, a warm and welcoming spot where my wife and I once had dinner with him and his wife. He visited Evert and Leida regularly. Behind all the visible work, there was this quiet thread of friendship – one theologian and two doctors, holding up a small hospital together, each in their own way.

When Evert and Leida arrived in 1960, Siloam was a modest mission hospital. Although officially recorded as arriving in 1961 as mission doctors sent by the Christelijke Gereformeerde Kerken, the memory of their early years at Siloam blends into a single truth: they came when almost no South African doctors were willing to serve there. Rural service was avoided, the workload was crushing, and the system fragile. Apart from one Venda doctor – later on – who was warmly received but soon left for private practice, the long-term continuity at Siloam rested almost entirely on foreign doctors who stayed not for status, but out of calling.

Over the years it grew, slowly and stubbornly, into a fully equipped district hospital. Like Elim, it became a place where medicine met faith, where improvisation met endurance, and where people survived because somebody refused to give up. Even after the hospital became a government institution, the missionary ethos never left. Doctors still travelled to distant communities on Sundays to preach. And behind our own house on the hospital grounds stood Siloam Church, where Venda ministers could preach for hours with joyful determination and only a faint sense of the clock.

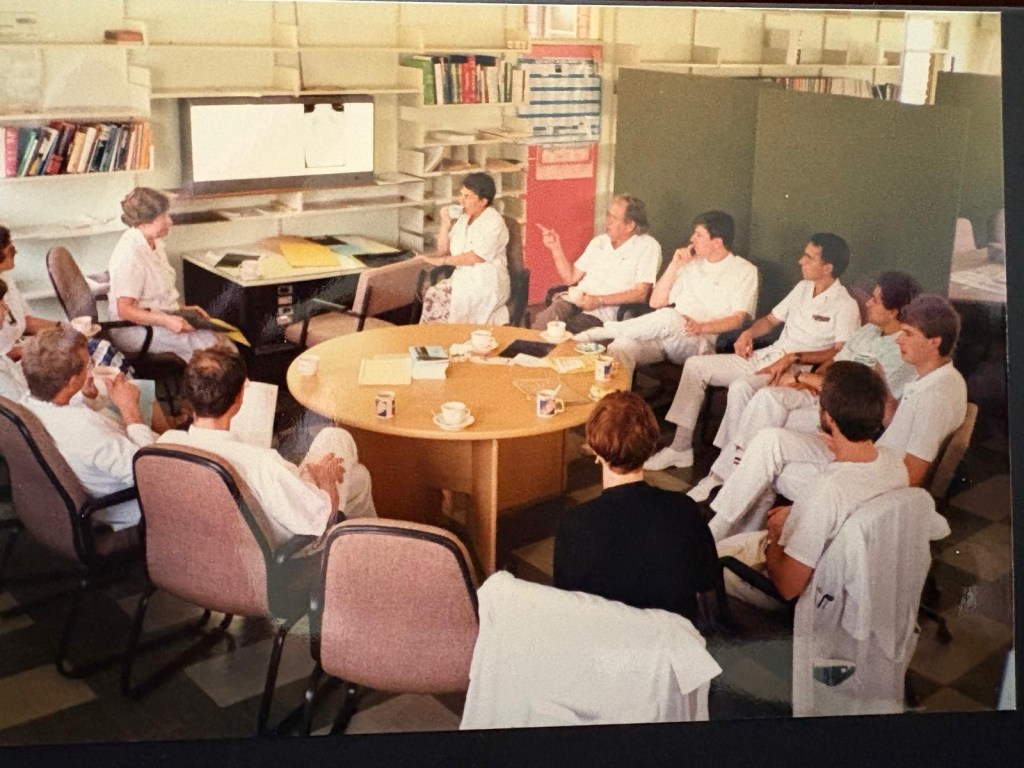

By 1989, when I arrived, Siloam had become a 500-bed hospital with outreach clinics spread across Kutama–Sinthumule. Our team included Gert Maritz, Paco Heymans, Frans Legemate, Jan Pieter and Annemarie de Kroon, Cor Roubos, Hans Timmer, Marijke Boele, and Loes (I forgot her surname). Some female doctors worked part-time. All doctors and nurses held the system steady, including the wonderful lab technician Maartje Kruger, the pastoral worker Mary, Philip and Christa (maintenance man) and myself. And then there was Leo Meyndert as well, dentist (and maxillofacial surgeon), whose skills were irreplaceable in a place where trauma and infection arrived daily.

In later years, after the upheaval at Siloam, Gert would become Medical Superintendent of Elim Hospital – one of the few who remained in South Africa, enduring yet another cycle of strikes and unrest with the same steady temperament that had anchored him at Siloam.

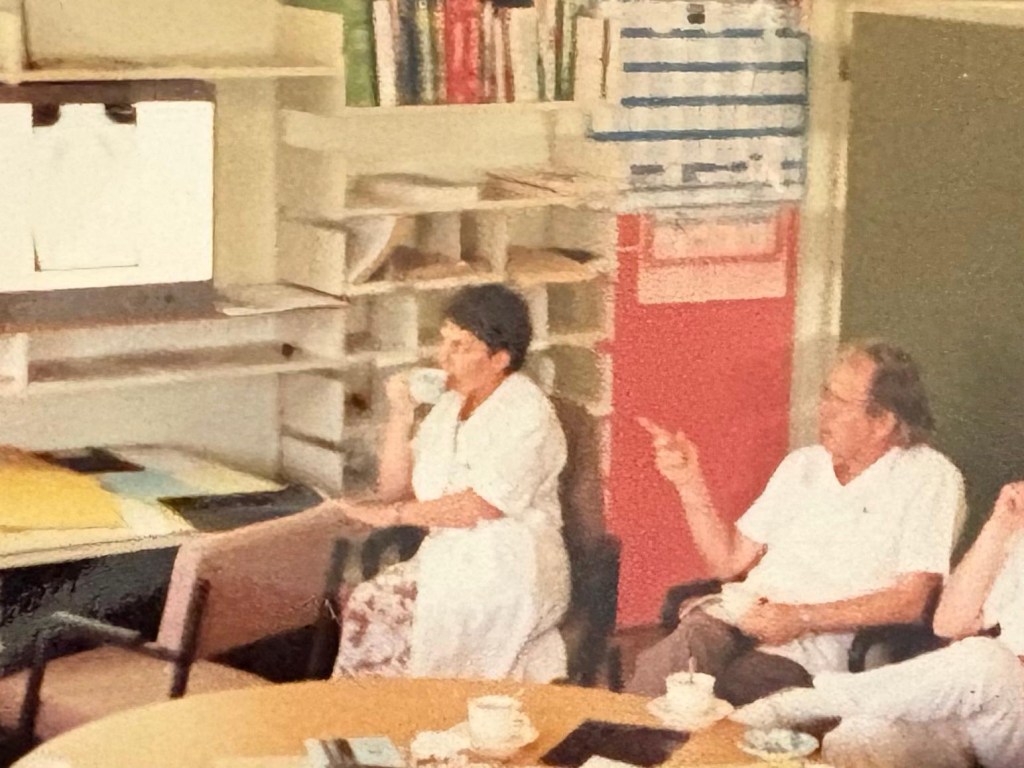

Our rhythm was strict and simple. Ward rounds at dawn. Then all doctors gathered in the doctors’ room – stale coffee, stacks of X-rays held up to the sunlight, tough cases discussed, a bit of laughter to brace us for the day. After that, we scattered: OPD, casualty, theatre, outreach. The full-time male doctors carried the night calls: first on call handled everything after 5 pm; second on call stood ready for a general anaesthetic or a C-section baby. When he reached forty, Gert Maritz was granted exemption from night calls. No one questioned it. He had earned the rest ten times over. Mass accidents never occurred during my time, but we lived as if they might.

What I remember most is that we were not merely colleagues – in a quiet way, we were a kind of family. Yes, there were misunderstandings now and then; every overstretched team has them. But they never lingered. Evert had a calm, down-to-earth way of lowering the temperature. On Sunday evenings, several of us gathered as families for Bible study and prayer. I still remember one evening when Evert read from Romans 8 – “we are accounted as sheep for the slaughter… yet nothing in heaven or on earth can separate us from the love of God in Christ.” It landed with a warmth I still carry. Life was hard at times, the country was changing, medicine was relentless – but that text gave us a moment of shelter. A small sanctuary before the week began again.

Hospital church

Looking back now, I realise that we belonged to a generation of clinicians who served in relative obscurity. The heroes around us – Evert, Leida, Jacques, Maritz, van Rooy – never stepped into the limelight, not because they were hiding, but because the work itself was enough. Today the world often tells a different story: visibility is seen as advocacy, and public witness has become part of the humanitarian landscape. I don’t judge it. It is simply a different era. But the quiet servants who held places like Siloam together for decades remain, to me, the truest measure of endurance. They asked for nothing, they received almost nothing, and yet they carried everything.

There is an old photograph of Evert and Koos van Rooy standing with the advisory council of Siloam Hospital around 1967 – a grainy, black-and-white image of two men who looked ordinary and carried entire systems on their shoulders. That picture captures what Siloam was: not a place built by dramatic moments, but by steady people who simply kept showing up.

Dr Helms led the hospital for decades, supported over the years by various and changing colleagues, each carrying their share of the work without seeking recognition.

But history is rarely kind to the people who hold the centre. By the early 1990s, the political climate shifted sharply in Venda.

What happened at Siloam in those years was not a failure of its people, but a breaking of the structure around them. The transition into the new South Africa brought hope, but also tensions that fell hardest on rural hospitals. Hard-line political factions stirred unrest among staff; old loyalties dissolved; administrative support evaporated. Evert received almost no backing from the Department of Health at the moment he most needed it. He once told me that this absence of support felt like a kind of betrayal – not personal, but institutional, as if the endurance that had kept Siloam alive for decades suddenly counted for nothing.

When the situation finally erupted, the departure was abrupt and painful. They had to leave fairly abruptly – with little time to prepare and no real chance to say goodbye. Decades of work collapsed in days. The system around them fractured, and the team that had kept Siloam steady scattered in all directions. Most of the doctors returned to the Netherlands. Mary, the pastoral worker, moved to Canada. Philip and Christa left deeply shaken. Only Maartje, the lab technician, remained until retirement. Later, when Siloam fell into disarray – with rotating overseas doctors, low morale, refusals to do on-call, and stories of drinking on duty – the Department of Health invited Evert to return. He declined. “I have no team,” he said. And for a man who had held an entire hospital together through unity and shared purpose, returning alone was impossible.

It was a painful ending to a lifetime of service. After nearly forty years, Evert and Leida were forced to return to the Netherlands. They didn’t want to leave; they simply couldn’t stay. When they reached the Netherlands, they settled quietly in Apeldoorn, Zevenhuizen, in a modest house that mirrored their character – grounded, unadorned, without the slightest sense of entitlement. They carried the weight of their sudden departure with a calm dignity, never bitter, but undeniably marked by the speed with which their life’s work had been uprooted.

Their children – most of whom settled later in Canada – carried Venda in their childhood memories. A few years later, while visiting his children there, Evert died from a stroke. A man who had given most of his life to a rural corner of South Africa slipped into history with little official recognition, despite a legacy carved into thousands of lives.

I served only eighteen months – a blink compared to their decades. My time ended abruptly when my wife became unwell, and we returned to Europe with our two young children. But those months formed me. They taught me what service looks like when no one sees it. They taught me that humour can carry people through impossible nights. They taught me that mission and medicine are sometimes the same thing.

After the fracture of 1991–1992, the world we had known at Siloam dispersed like a constellation losing its shape. Some returned to Europe, some remained in South Africa, some carried their memories across oceans. The story of Siloam did not end because its people failed, but because the conditions around them changed faster than any of us could hold together. And yet the imprint of those decades remains: a quiet, unpublicised faithfulness that lived in theatres, in clinics, in Bible studies on Sunday evenings, in small acts of endurance nobody photographed or recorded. Even in their absence, Evert and Leida’s work continued to live in the health systems, families and communities they served.

I write this not because nostalgia is pleasant, but because remembrance is justice. Some people serve for a moment and are celebrated for years. Others hold a region together for forty years and are forgotten in three. But those of us who were there know the truth: Siloam was built on the backs of Evert and Leida Helms and the people who stood with them.

Not all giants stand tall.

Some simply stand long.

And the world is better because they did.

Even when they seem forgotten, our work, preferably not in the limelight, still counts.

——————

Epilogue – The Cost of Service

There is a part of this story that is rarely spoken about, yet it belongs to the truth.

When Evert and Leida returned to the Netherlands after nearly forty years of service, they did so without the financial security that many people their age take for granted. Mission doctors of their era received no pension fund, no government superannuation, and no transition support. They returned quietly to a modest house in Apeldoorn-Zevenhuizen and lived with the same simplicity that had defined their years in Venda.

Had Evert chosen another path – had he become a surgeon in the Netherlands, or built a career in private practice – life would have been very different. Comfort, recognition, financial stability: all of it could have been his. But he chose a different road, and he walked it with a steadiness that did not seek reward.

The cost of service is often invisible.

And yet it is precisely this hidden cost that gives their story its weight.

They did not accumulate wealth; they accumulated lives saved, wounds tended, families held together, and a hospital kept standing long after it should have fallen.

In the end, their legacy is not measured in pensions or possessions, but in the quiet fact that a region survived because they stayed.

Some people are rewarded for what they achieve.

Others are remembered for what they gave up.

Evert and Leida belonged to the second kind – the rare kind.