Let’s start with the archives—because what’s a family story without a few centuries of paperwork?

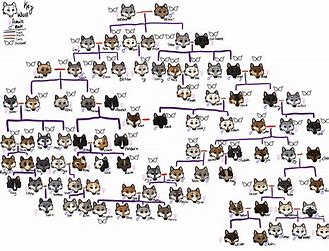

The Wolf family has been around for quite a while—at least since the 17th century, when Elias Wolf (born in 1717 in Rostock) became the Mayor of Jever. As a proper overachiever, he married Margarethe Christiene Kohnemann, and together they produced another Elias Wolf (because originality in baby names wasn’t a strong suit back then). This second Elias, born in 1768, decided that life in Europe was too ordinary, so he ventured off to Essequebo (now Guyana), bought some plantations, and took a role as President and Adviser in the Criminal Justice Department—presumably putting the “Wolf” in “law and order.”

In 1792, he married Sarah Barkey in Rio Essequebo, and they had five children, one of whom was Frederik Hendrik Elias Wolf (because, again, why not reuse names?). Born in 1803 in Breda, he decided to swap tropical plantations for the pulpit, becoming a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church—because every family needs a reverend, just in case. He married Johanna Henrietta Coenen, and they also had five children (because small families were clearly not a thing). Among them was Elias Frederik Hendrik Wolf (born 1829), who also became a reverend. He married Sophia Carolina Charlotte van der Goes, and together they produced seven children, one of whom would become my granddad.

Now, considering the diverse career choices of his brothers and sisters, I can only imagine that my grandfather, Louis Gustaaf Wolf, came from a rather “colourful” family. Born in Klundert in 1865, he showed early signs of defying expectations. He started studying medicine but, in a move that probably gave his father heartburn, he quit in his fifth year—just before the clinical part—because he realized he didn’t actually want to be a doctor. (Cue a dramatic family meeting, no doubt.) Instead of switching to a more “respectable” career, he decided to follow his own path.

How he met my grandmother, Louise Ploos van Amstel, remains a mystery, but in 1899 they tied the knot. Then, just to shake things up, they moved to Canada around 1900 and helped establish one of the first Dutch settlements near Yorkton, Saskatchewan. Maybe granddad wanted some distance after his unconventional career move, or maybe he just liked adventure. Either way, my Aunt Sophia was born there—surrounded by real wolves, Indigenous communities, and all the ruggedness that early Canada had to offer.

However, my grandmother was not built for the Canadian wilderness. After a few years of enduring the harsh climate and presumably missing Dutch cheese, she became terribly homesick. Thus, the family packed up and sailed back to the Netherlands. Had she not been homesick, my entire existence—and this story—would likely have taken place on the Canadian prairies instead of here. A fun “what if” to ponder.

Once back in the Netherlands, granddad needed a solid job, so he joined the N.V. Maas-Buurt Spoorweg (Maas-Buurt Railway Company). By 1918, after the First World War, he climbed the corporate ladder and became the President-Director. Imagine running a railway company while dealing with post-war economic chaos, the rise of bus companies stealing passengers, and the need for major social reforms. Sounds stressful, but granddad thrived—leading with energy, fairness, and a good dose of humour.

He retired in 1935, but life wasn’t about to slow down. During World War II, both he and grandma sheltered Jewish families in their home in Bussum. This was especially risky given that their own son—my dad—was actively involved in the Dutch resistance.

The Resistance, Betrayal, and a Narrow Escape

Now, my parents met under very dramatic circumstances. My dad, part of the “Flying Brigade” resistance group, was busy sabotaging the Nazis, while my mum worked as a courier—smuggling messages, documents, and intel to the Allied Forces. Naturally, this made them both prime targets for the Gestapo.

In fact, their entire resistance group was betrayed and captured—except for my parents, who survived purely by luck (or divine intervention). My dad had been about to attend a crucial meeting for planning an assassination on a high-profile Gestapo officer. But something felt off. First, his second-in-command didn’t show up. Then, on his way to the meeting, he noticed too many police cars outside his friend’s house. And then—just before walking into the meeting—my mum and the minister’s wife physically stopped him. Turns out, the meeting was a trap, and everyone inside was captured and later executed.

This narrow escape meant my dad spent the rest of the war in hiding. After the war, in a twist of fate, he found himself cross-examining the very Gestapo officers who had murdered his friends. It must have been a bizarre experience—part justice, part personal reckoning.

After the war, my parents married, but their relationship, shaped by trauma, wasn’t built to last. They separated 26 years later, but despite that, they both left their mark—not just on history but on their children.

Childhood, Haamstede, and Learning from Life

Growing up, I had many good influences—some near, some far. Some I never even met but whose impact shaped my thinking. The most enduring childhood memories revolve around summers in Haamstede, a beautiful coastal village where we spent countless holidays.

My dad, despite his war scars, was always eager to show me historical sites, old churches, and tell me stories. He had a deep love for the past, which probably explains my own fascination with history. Meanwhile, my mum—ever the practical one—was in the kitchen, cooking while the sun streamed in through the windows.

Family life wasn’t always smooth, of course. School had its challenges, especially under a headmaster who believed in the power of “educational discipline” (read: he used his hands when he thought kids were naughty). Secondary school was a mix of trouble and distraction, not helped by my parents’ divorce. But things changed when I moved to a foster family in Apeldoorn. This family—warm, artistic, and slightly unconventional—gave me the support I needed to focus.

After finishing school, I took a somewhat unexpected turn. I first trained as a teacher before deciding medicine was my real calling—ironic, considering granddad quit medicine five years in. Unlike him, I pushed through, got my qualifications, and built a career that took me across the world—from the Netherlands to Scotland, England, and even South Africa.

The Bigger Picture

Over time, I’ve realized that life isn’t just about examples—it’s about the example. Small moments, small acts of kindness, and small seeds of wisdom planted when we least expect it. Many people—family, friends, and even strangers—have shaped me in ways they never knew.

And while life is unpredictable, full of what-ifs and unexpected turns, there’s one thing I’m sure of: If my grandma hadn’t been so homesick for the Netherlands, I might have been a Canadian cowboy instead of writing this story from Australia.

Funny how history works, isn’t it?

Paul Alexander Wolf